|

You are here: Home ~ Websites ~ It's Pretty But I Can't Use It

"It's Pretty but I Can't Use It"

Why People Complain About Web Sites

Copyright 1999 by Susan Fowler, Victor Stanwick

Introduction

"It's pretty but I can't use it." Have

you heard someone say this about your site?

People also say things like, "This website

loads too slowly!" or "I get lost in this

site!" or "There's nothing here I'm interested

in!"

Web design is not like page design or even like

GUI design....

In this article, we will tell you things that you already know from

experience--you already know what the problems are.

But you may not know why they're problems

or you may not know what to do about them.

We intend to give you the information you need to

create usable pages and, if necessary, to defend

your choices in design and client meetings.

Standards

and Defaults

Colors

Color theory and much research have shown that red

is a very poor background color. There was a certain

web site that we were going to use as an example of

what not to do, but fortunately (or for the purposes

of this web site, unfortunately), they fixed the

problem since this page went into production. They

violated the following standard: they had a red background

with blue text. Look at the table below for an example

of what this does to your eyes.

Red

background, blue text...

Your

eyeballs are probably wiggling around

inside your head as you read this. Imagine

if you had to stare at this color combination

for an extended period of time? |

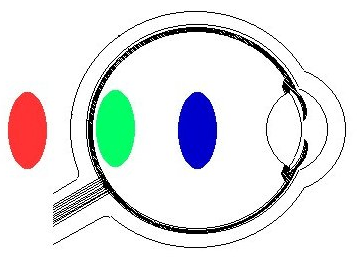

The reason the color combination above hurts is because

of the way the human eye focuses color wavelengths:

- Red wavelengths come into focus a little behind the

retina, so reds appear to pop out of the background

and come at you.

- Yellow and green wavelengths (as well as black and

white) come into focus at the retina and require the

least accommodation.

- Blue wave lengths come into focus a little in front

of the retina, so blue appears to fade into the background,

away from the eye.

For these reasons, blue makes a great background color.

You can use red if you want something to jump out at

the viewer. However, too much red text on a blue background

(or vice versa) will still cause your eyeballs to wiggle.

For foregrounds and text, yellow, green, black and white are best--they're as visible

on the periphery of your vision as in the center of

the visual field.

Color Confusion

One very important thing to consider when working

with color: Eight percent of males (that's every twelfth

male) are red-green color-blind.

The term "color-blind" is

a little misleading. Many men who are color-blind can

actually see the colors red and green when they are

used separately. However, when the two colors are next to each other, they have a tendency to "melt" together

and become indistinguishable. The key to avoiding this problem is using more than color to carry information. For example, on a chart, use a dashed line and a solid line; they can be red and green if you like, but the difference between them is reinforced by the style of line.

For one of the best articles anywhere on color confusion,

see Color

Vision, Color Deficiency by Diane Wilson.

Wilson's TRICHI logo works even if you're

color-blind because

the colors have enough contrast

to stand out from one another.

Printing Colors

The web site for the First

International Software Assurance Certification

Conference, held in 1999 at the Marriott hotel in Dulles, Virginia,

had a greenish background with white text. The page contained important

information, and it is likely that many people printed it out. Or tried

to.

However, depending on the web browser they were using,

when they printed the page they may have ended up with only the

ISACC'99 logo and the title graphic at the top of the

page. Why is the rest of the printed page blank? Because

they asked their printers to print the text, and the text on the web page is white!

Both Netscape and Internet Explorer have print settings

window where you can set an option to print text in

black or print background colors and images. However, most users don't know about that window and wouldn't think to look for it.

Nicholas Zvegintzov alerted us to this particular

problem. And the color problem wasn't the only thing he found

wrong. Once Zvegintzov changed his print settings and

finally got the page to print, he discovered that the

top page had a WIDTH command in the HTML code, so it

wouldn't fit either on the screen or on the printed

page. Did the person who coded this page take lessons

on how not to be understood? By hardcoding the table

width to that of a high resolution monitor, the table

cannot be resized to fit the paper or the screen.

Suggestion: Offer your users a CSS for printing, a "printable" version of the page (just an HTML file reformatted for printing), or a PDF, especially if you feel you really need to create hard-coded

tables and especially if your web document spans more

than one web page (if a web article is on more than

one page, the reader has to print

each page separately).

Accessibility

Accessibility means access for everyone.

For instance, if you add alternate text (tool tips)

to the graphics on your web site, screen-reading applications

can read them aloud for blind or partially-sighted

users. What is alternate text? It's what you see if you place the cursor over

any of the graphics on this page (such as the "Top

of Page" pointer above). A small yellow box appears

with the description of the graphic in it (you have to write these for each graphic).

Making pages accessible also means accommodating

different web browsers. For example, FireFox doesn't

recognize ALT tags. If

you are designing and testing web pages using Microsoft's

Internet Explorer, also check them against FireFox, Safari, and Opera. Chances

are that some of these users will have difficulties with

your pages.

Navigation is Everything

Splash Screen Overload

Some web sites use "splash"

screens as their first pages. While some

of these splash screens are lovely to look at, such

as the Panama

Canal Web Site, they require significant amounts

of time to load.

Splash screens were invented for desktop applications.

Software programmers realized that they could stop people

from complaining about long load times by giving them

something interesting to look at. In other words, splash

screens were used to mask a loading-time problem. But

by putting a splash screen on a web page, web programmers create a loading-time problem. So don't do it--instead,

open your site with your real home page.

To Scroll or Not to Scroll

Newspapers originally coined the phrase

"below the fold" to indicate news items that

were important enough to appear on the front page, but

not important enough to show up at the top. These articles

appeared below the fold (where the paper was folded

in half).

Web sites work much the same way. The

information that appears at the top of the home page

is the information that people are going to read first.

However, Jared Spool found that people didn't mind scrolling

down a web page as long as they could tell that there

was something interesting below the fold. (His research

is described in Web Site Usability: A Designer's

Guide.) What he also found, though, was that

if readers didn't know there was something below the

bottom, they didn't scroll down.

Where Do the Navigation Buttons Go?

Jared Spool discovered that, even when a command button

was in the middle of a page and the reader was staring

right at it, she sometimes dropped down to the bottom of the page

and used the buttons there when she was ready to buy.

He didn't have an explanation, except to guess that the reader had been trained to do so by Windows dialog boxes, but the moral of the story is: Always repeat your buttons at

the bottom of the page.

Spool also found another reason to put navigational

aids at the bottom of pages--what he calls the "seducible

moment." Only after the reader has read the entire

article or review will she pay attention to advertising.

At this point, she's ready for more--ready to buy the

advertised product or book. See Seductive

Design for Web Sites for more information.

Raise the Data

to Ink Ratio

Restricted View

Looking at a web page versus a printed page is like

looking through a telescope versus looking with the naked eye. With a telescope,

you can only see one piece of the sky at a time—a small piece

of a much larger picture.

The resolution on most computer monitors is about

50 dpi (dots per inch). The best monitor resolution

is only about 72 dpi. However, the resolution of type

on a printed page is usually 1200 to 2400 dpi.

50 dpi, 100 dpi, 2400 dpi. Which one holds

more data?

For the level of detail you can get on an 8 1/2"

x 11" piece of paper, you need screen after screen

on the computer. What you can't see all at once, you

must see over time...

Raise the Ratio: Comparison Shopping

Jared Spool asked his usability test participants to

compare two things. He said they usually ended up printing

out pages, writing down notes, and using the Back and

Forward buttons on the browser. Only one person thought

to open two browser windows at the same time.

Companies with products that are able to fill more

than one need may want to make it easy for users to

compare those products. For example, Hewlett Packard

makes several different kinds of printers, many of which

are capable of performing more than one function. There's

a pretty big difference between functionality and pricing

among their line of printers. HP made it easy for their

customers to compare their products on most of their product web pages (for example, look at the business laptop comparison pages). Travelocity.com uses this same comparison technique

to help users buy airline tickets at the lowest possible

price.

Raise the Ratio: Wrapped Links

One of the biggest mistakes web designers make is creating

long columns of hypertext links that "wrap"

to a second (or even third) line. If there is no spacing or bullet points to separate the links, readers have no clear idea of where one link

ends and the next begins. It's pretty easy to fix this

problem, though--just look at Fidelity Investment's home page. The left navigation is a column

of hypertext links, but they're separated by bullet

points. It makes for a neat and easy to understand

site.

While we're on the subject of hypertext

links, let's look at the Disney web site. At Disney Travel, the links don't give you a clear idea

of where they'll take you. In the case of Disney, maybe this doesn't matter--DisneyWorld and DisneyLand are supposed to be magical places that you enjoy exploring.

But if you're trying to buy a car, you don't want to explore. In contrast, the hyperlinks at Edmunds.com tell you exactly what you will find when you click the

link. They are clearly labeled and easy to use.

Raise the Ratio: Internet vs. Intranet

vs. Extranet

On an Internet site, you must provide obvious navigational strategies like bright colors for important information and arrows or supersized buttons to indicate what readers should do next. Most

readers generally don't visit Internet site for long periods

of time--they find what they are looking for and move

on. Since they are in "uncharted" territory,

they will need more help up front than they would while

using a familiar application.

Intranet sites, on the other hand, can be more subdued. People will be using an intranet site

every day, and after a while they will notice every

little detail.

If you have an extranet site, such as the FedEx

tracking site where authorized users log on to

the system, consider mimicking the customer's branding instead

of displaying your own branding.

Elegant by

Design

Citibank's Original Americans with Disabilities

ATM Design

Note: The ATM design described in this 1990s article (adapted from ID magazine) no longer exists. Many banks have switched to talking ATMs instead, and online banking makes it easier for blind and partially-sighted users to do most of their banking using their own computers and screenreaders. So although the solution described below was a good solution, it wasn't the only solution. Adapt as needed. --Susan Fowler, 2008

Most American banks had no problem making their ATM

machines accessible to their vision-impaired customers.

In most cases, all the banks had to do was stick Braille

labels on the already existing machines. Many banks

didn't have to change any hardware at all.

Everyone in the industry was waiting to see what would

happen to Citibank, with their touch-screen ATMs. They

would either have to make some machines available with

standard buttons (and Braille labels), or remove all

of their existing ATMs and replace them with something

new. A great expense any way you look at it.

However, instead of replacing all of their ATMs with

some different model, Citibank asked its vision-impaired

customers what they would like to see.

With their customers, a team of Citibank programmers

in California and a usability engineer in New York,

plus designers at Two Twelve Associates in New York,

Citibank came up with a brilliant solution to the problem.

This solution not only made the ATMs accessible to the

largest possible number of users, but it was a much

better solution than simply pasting Braille labels on

button pads.

Here's what they did.

The problem...

Citibank's ATM machines use a touch-screen to perform

transactions (there are no physical buttons on the ATM).

A person with vision problems may not be able to read

the screen well enough to use the ATM. Citibank did

some research and found out that many (in fact

most) Americans with vision problems do not read Braille.

The totally blind may read Braille, but the majority of vision-impaired people

still have some vision. Therefore, the Braille

labels on most bank's ATM machines are not doing these

customers much good.

As you know from reading the information presented

in other sections of this web site, the best possible

contrast is black and white. The folks working on the

Citibank ATM problem knew this and used it to their

advantage.

The solution...

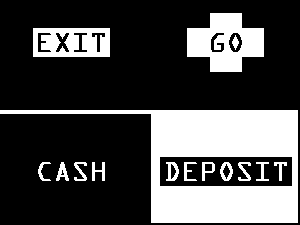

Citibank designed new interfaces for their touch-screen

ATMs. They designed interfaces with black backgrounds

and large white text buttons (a white background with

black text would have been too bright, their sources said--it was like trying to

read the label on a burning light bulb).

The basic look of the touch screens is completely different

from the "normal" screens that most users

see when they visit an ATM:

Citibank's ADA ATM touch-screen.

The vision-impaired user taps the words on the screen

to run through transactions. The ATM responds with tones

appropriate to the interaction--for example, one note for OK, a short falling tune for errors. (Citibank sends a pamphlet to its vision-impaired users explaining how to use the ATM and there is in-bank training as well.)

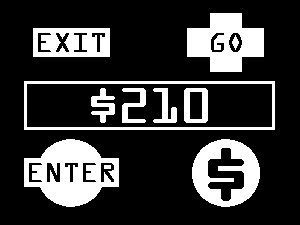

If the user taps CASH or DEPOSIT on the screen above,

a new screen appears on which the user can specify the

amount to deposit or withdraw (see the screenshot below).

The deposit/withdraw touch-screen.

Tapping the large dollar sign in the lower right corner

increments each digit by one. "Enter" means "zero" in this context. For example, to withdraw

$210.00, you would tap the following sequence:

$ $ ENTER $ ENTER ENTER

GO

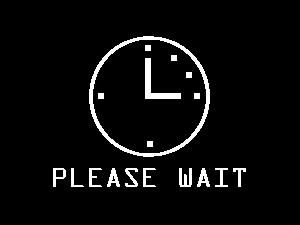

The ATM lets you know that it's processing the transaction

by showing you a clock and playing a ticking noise.

The transaction is being processed.

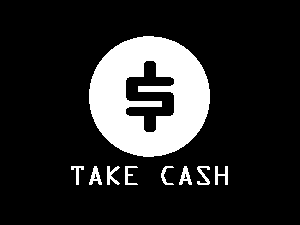

When the ATM is ready to dispense the cash, you hear

a three-part tone and the screen tells you to take the

cash (below).

The ATM has finished the transaction.

After you have completed all of your banking transactions

and signed off, the ATM thanks you by playing a 7-note

(major triad) tune (below). Vision-impaired users who were employed

to test the ATMs said at this point, "Oh, it's

saying 'Good-bye!'"

Citibank ATMs are nothing if not polite.

|